7 blind spots in vulnerability scanning

.png)

Modern security programs rely heavily on vulnerability scanning. Containers, operating systems, and third-party dependencies are all swept through automated scanners designed to surface CVEs that could be exploited. On paper, the model works well: run a scan, get a list of vulnerabilities, and patch accordingly.

But the reality is more fragile. A scan that returns “0 CVEs” often feels like solid proof that an image is clean and secure. But in reality, it may just be proof that your scanner didn’t see what was really there.

Blind spots in advisory data, mismatched metadata, or even internal scanner errors can all combine to make vulnerabilities disappear in scans, while they remain very real in production.

At echo, we’re building clean, CVE-free images from scratch every day and validating them across all major scanners. This means we have first-hand visibility into not only how scanners detect vulnerabilities, but also where they break down. Every time we analyze why one scanner may flag an issue that another doesn’t, we uncover more about the fragile ecosystem these tools depend on.

This unique vantage point has made us experts in the ins and outs of how scanners work and where the cracks inevitably appear. That’s why this ebook explores today’s scanning ecosystem and highlights seven critical blind spots we’ve discovered. We’ll explain why a clean report doesn’t always mean a clean environment, and how teams can move toward eliminating these blind spots at the source.

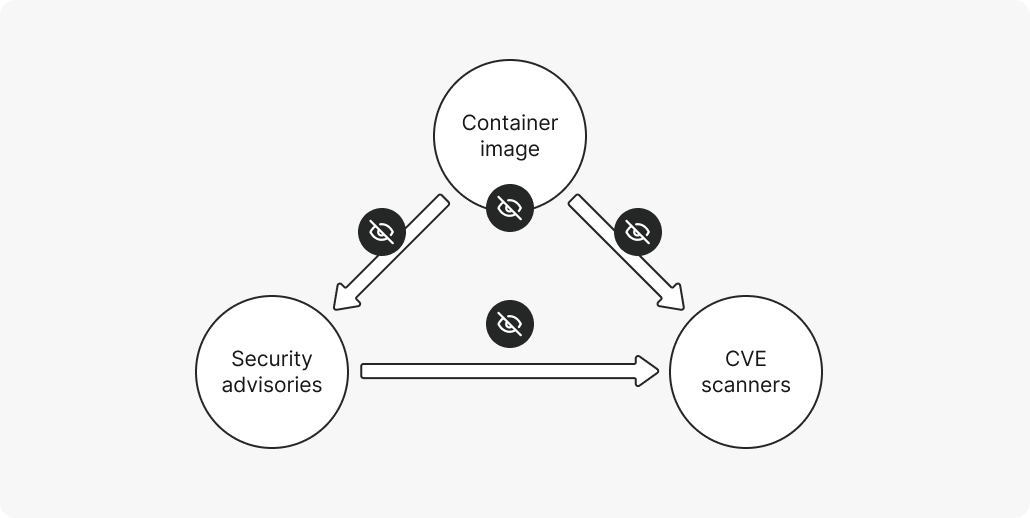

The fragile software triangle

Effective container scanning rests on a three-part structure – a fragile triangle made up of the container image, the security advisories, and the scanners. Let’s break each one down.

The container image:

The image is the actual file system that runs in production. It’s built layer by layer, and each layer can introduce new components. Inside a typical image, you’ll find:

- System packages: OS-level components installed via package managers.

- Runtime environments: Programming language interpreters, such as python and Java.

- Application dependencies: Libraries and frameworks from ecosystems.

- Application code: Custom binaries and business logic that make up an application.

- Metadata: Labels, environment variables, and runtime instructions.

- Configuration files: Settings that determine permissions, security posture, and behavior.

The layered nature of container images means both vulnerabilities and sensitive information can be introduced, or masked, at multiple points in the build process.

Security advisories:

Advisories are the feeds that explain which CVEs exist, the versions they affect, and how severe they are. They come from sources like the National Vulnerability Database (NVD), GitHub Security Advisories, and distro feeds such as Debian or Alpine. Their job is to collect CVEs, analyze the security implications, determine affected software, and publish that information for public visibility.

Each source has its own focus. GitHub advisories excel at covering open source and language-level packages, while distro advisories concentrate on OS components.

It’s also worth noting that advisories are only as reliable as the upstream bug trackers and maintainers they draw from. So, when responsibility is murky, some CVEs get published but never properly resolved, leaving security teams wasting time chasing ghosts.

CVE scanners:

Scanners are the tools that turn this data into actionable findings. They analyze container images through a systematic process, which includes:

- Breaking down the image layer by layer to inspect the filesystem.

- Identifying the software that's been installed via package databases, binary analysis, and manifest files.

- Matching components against advisory databases using version comparisons and CPE mappings.

- Assessing risk severity and exploitability in the specific container context.

Scanners employ sophisticated techniques to minimize errors or false positives. Still, however, there’s a key limitation: scanners can only detect the CVEs they're programmed to recognize – and only in components they can effectively identify.

So, why is the triangle so fragile?

The fragility lies in dependency. If one component is missing something, the others typically don’t compensate for it, creating significant blind spots and tilting the entire system out of balance.

A false sense of visibility

In the world of vulnerability management, visibility is the promise that scanning tools make – if something is vulnerable, you’ll know about it. True visibility would mean every exploitable issue is surfaced, correctly classified, and mapped back to the systems it affects. It’s the foundation security teams rely on to prioritize risk and make patching decisions.

But in practice, the visibility scanning provides is partial and fragile. Clean reports often feel like proof of security, when in reality, they may only prove that the scanner didn’t see the problem. Gaps in advisories, missing metadata in images, and bugs in scanner logic can all suppress findings without warning.

Rather than showing up as messy or confusing reports, the errors are typically silent.The scans tell you everything is fine, which is what makes them so dangerous. Teams trust clean scan results, and real exposure stays hidden until it’s too late.

7 critical scanning blind spots

The following sections unpack seven recurring blind spots that we’ve observed while building, testing, and validating images across all major scanners.

#1: The distro advisory trap

Each Linux distribution maintains its own security advisory, which is responsible for collecting vulnerability information from researchers and upstream sources, such as the NVD, and deciding whether those issues apply to the distro’s software.

This process requires the distro to triage each CVE, analyzing whether the vulnerability is relevant to their specific builds. It’s common for multiple distros that include the same OS library to compile and use it differently, which means the security impact of a CVE can vary significantly depending on how the library is packaged, configured, or integrated.

Once a CVE is determined to be relevant, the distro must also assess its properties, like severity, exploitability, and whether any existing mitigations apply. This enables the advisory to reflect an accurate risk level for that environment. This information is critical because CVE scanners rely heavily on distro advisories to determine what’s vulnerable and how serious it is. There’s no better expert than the distro that ships the software, and scanners trust their assessments by default.

But this process is far from perfect. A large part of it is still manual and prone to delays, inconsistencies, and oversights. In the wild, we’ve seen:

- CVEs that take too long to appear in advisories

- Distros that only publish patched CVEs, not unfixed CVEs

- Severities that are incorrectly lowered

- Vulnerabilities that are wrongly marked as "not affected"

- Vulnerabilities with wrong affected version/fixed version

- Vulnerabilities that are only relevant for a VM or server – resulting in false positives

These blind spots leave companies exposed to risks they don’t even know exist. And because every distro has its own standards, timelines, and SLAs for security updates, what’s acceptable to the advisory might fall short in commercial or production-grade environments. After all, when a critical CVE is published, you don’t want to be the one manually patching your stack while waiting for an advisory to catch up.

#2: Missing or incomplete CPEs

Many depend on Common Platform Enumeration (CPE) data to decide whether or not a vulnerability applies to a specific piece of software. So, when an advisory, especially from the NVD, omits or mislabels that information, scanners can’t make the match. This means that the vulnerability still exists, it’s still public, and it may even be exploitable in your environment – but to your scanners, it’s invisible.

And this isn’t an occasional oversight. It’s systemic.

As of early 2025, NIST reported a backlog of more than 25,000 CVEs awaiting enrichment, with CPE population among the most time-consuming steps. Platforms like VulnCheck and Securin confirm that critical vulnerabilities are routinely published without the metadata that vulnerability scanners rely on.

Part of the problem is that assigning CPEs is genuinely difficult. It requires nuanced judgment about which software is affected, the versions in scope, and the context. Even seasoned analysts get it wrong, and the NVD doesn’t scale well to the volume of CVEs being published today.

The result is a dangerous lag between disclosure and detection. While the database is busy catching up, attackers may already be exploiting the very vulnerabilities your scanner can’t see.

#3: Scanner evasion via tampering

Each distro maintains a file that lists all of the operating system packages installed through its package manager. For example, Alpine uses /lib/apk/db/installed, while Debian and Ubuntu use /var/lib/dpkg/status, and Red Hat uses /var/lib/rpm/packages. CVE scanners rely on these files to identify what’s inside the image and then match those packages against known vulnerabilities.

But what happens if the metadata is wrong? If a file is accidentally deleted or intentionally altered, scanners are effectively blinded. The vulnerable package may still exist in the filesystem, but without its entry in the package database, scanners have no way to flag it.

This isn’t just a theoretical risk. Attackers can exploit it deliberately, scrubbing metadata as a way to hide vulnerable components from automated detection. Even without malicious intent, tampering happens in practice – especially in custom images where layers are slimmed down aggressively.

The result? Scanners assume nothing is installed, report a clean image, and vulnerabilities sit quietly in production. It’s a blind spot created not by the CVEs themselves, but by the scanner’s reliance on fragile metadata to see them.

#4: Internal parsing issues

As we mentioned earlier, the fragility of the triangle can stem from any of the components, including the scanners. They have to parse operating system names, map package versions, and analyze filesystem layers – all tasks that can present issues. While you may get a scan back with 0 CVEs, in reality, it doesn’t necessarily mean your image is secure.

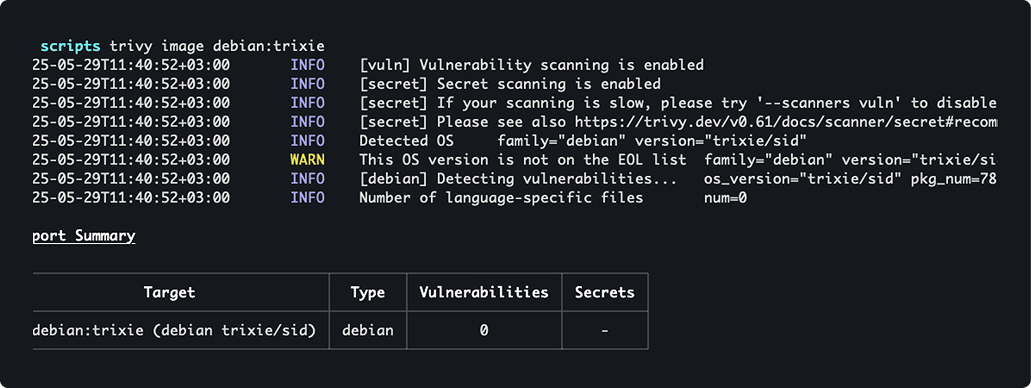

Let’s break it down with a real-world example.

Scanning the latest debian:trixie image with Trivy reveals dozens of CVEs – some with no available fixes. However, when you scan its “sid” version, zero CVEs show up…

You might ask, how could the sid version report 0 CVEs when the stable version still shows dozens of unfixed ones?

Well, after digging, we found that Trivy has an internal issue when it comes to showing vulnerabilities for the sid version for Debian. But instead of failing the scan, it simply shows 0 CVEs without any mention of an error or warning.

#5: Software installed outside the package manager

While package managers like apt, yum, and apk give scanners a structured record of what’s in an image, it only really works if the software was installed using the package manager. Most official Dockerfiles install OS dependencies using the package manager, but take the main component from another source when building the image.

These components never appear in package metadata, which leaves scanners with no reliable way to detect them. The result is a major blind spot. If the scanner can’t identify the software, it can’t flag the vulnerabilities it carries. The code or binary may still be in the image, but it remains invisible to the scanner – and the risks go unreported.

For example, a team might build an image that includes Node.js by manually copying a binary into /usr/local/bin To the scanner, that Node runtime doesn’t exist, so any CVEs affecting that binary will never appear in the report.

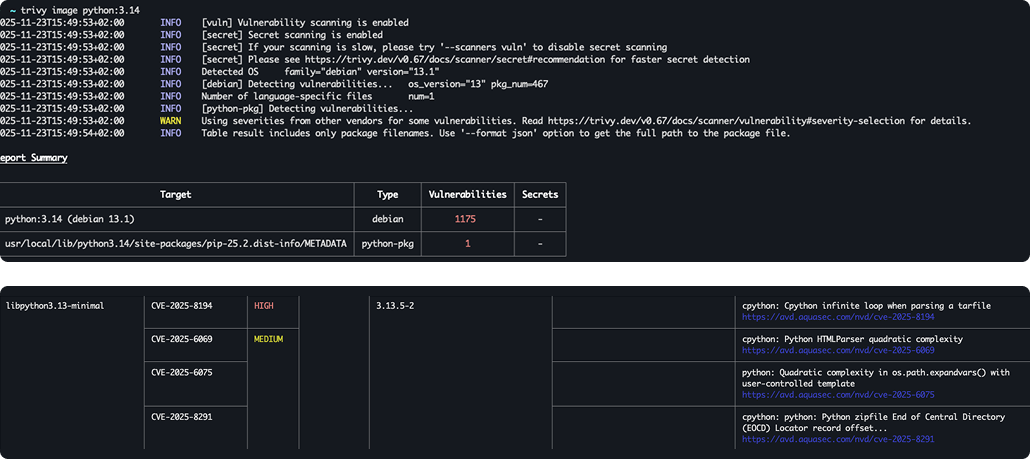

A similar issue occurs with the official Python image. It’s built on top of Debian, which already includes a different system Python installation. When scanners analyze the image, they detect Debian’s default Python version, rather than the newer runtime actually used in the container. As a result, scanners surface vulnerabilities for the wrong version and completely miss those affecting the one that’s actually running.

#6: CVEs lost in upstream limbo

In all of our scanning, we’ve come across another major blind spot that comes upstream. It’s not about scanner issues or missing metadata, but rather, a lack of ownership.

See, most modern software relies on long-standing codebases, which have been passed from maintainer to maintainer over many years – if not decades. As time goes on, this transfer of ownership has increasingly blurred the maintenance and security responsibility.

This means some CVEs wind up in a sort of limbo – neither clearly owned nor consistently tracked. The result? Users are exposed, and maintainers are unsure who needs to fix it.

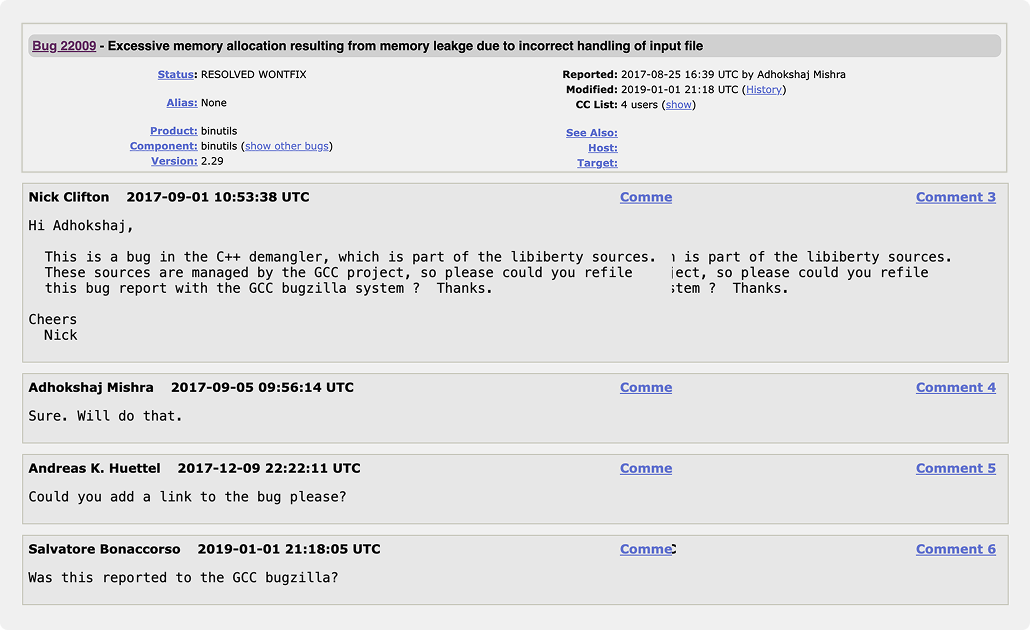

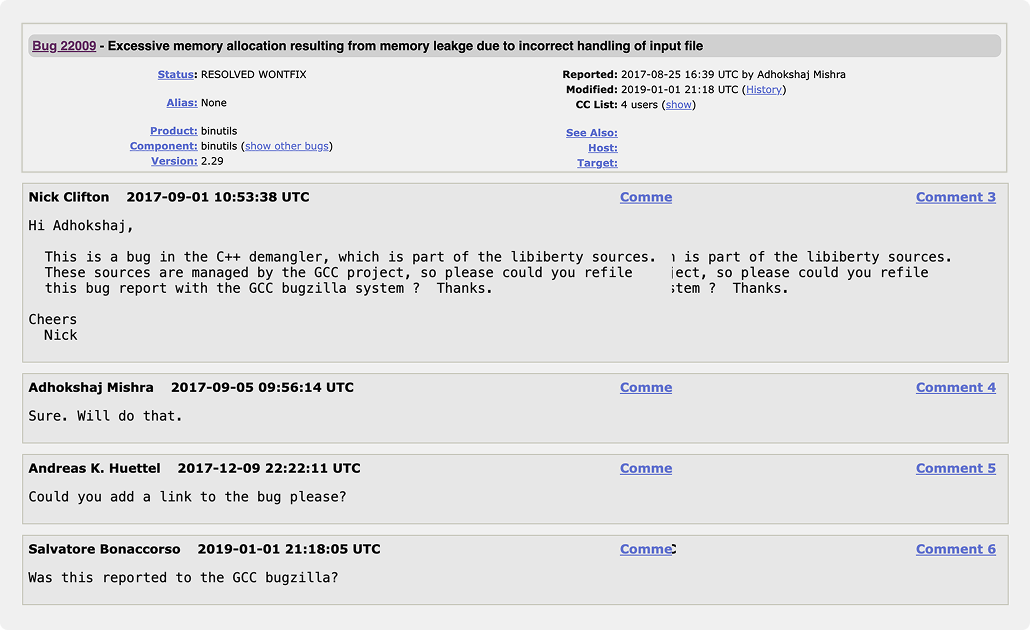

Consider the case of CVE-2017-13716, a memory leak in GNU libiberty. When this CVE was published in 2017, it was assigned to binutils even though GCC was the actual custodian. The reporter was instructed to notify GCC, but the refiled bug never happened.

As a result, no official patch was ever linked to the CVE. The bug remained in “limbo,” marked “RESOLVED WONTFIX” in binutils, persisting as an open entry in MITRE’s database. It still shows up in scanners today, even though it’s already been quietly fixed upstream.

When accountability is unclear, especially in long-lived code that’s shifted across projects, vulnerabilities can be recorded but not necessarily resolved. Scanners will dutifully report them, but without any specific ways to flag them. And your team may be chasing ghosts, disrupting prioritization, and confusing incident response.

#7 Internal logic variance

Even when advisories, metadata, and package information are complete, scanners can still disagree. Each tool uses its own internal logic to determine which vulnerabilities apply, which data sources to trust, and how to map CVEs. The result? Two scanners analyzing the same image can produce completely different results – not because one is wrong, but because they interpret the same inputs differently.

For example, while some scanners fully rely on CPEs, others don’t reference them at all. Instead, they depend entirely on the distribution’s security advisory to decide which CVEs are relevant. That means the scanner inherits the distro’s blind spots by design. Trivy, for instance, relies on advisory feeds, and since Alpine only lists CVEs that have already been fixed, Trivy may report a “clean” image even when unfixed CVEs are present upstream.

This internal logic variance is easy to overlook because it’s invisible from the outside.A scan result doesn’t show which data source or matching algorithm was used; it only shows a list of findings when applicable. For security teams, this means scanner choice is more than a tooling preference – it fundamentally shapes what you see as “secure.” And without visibility into each tool’s assumptions and logic, you might trust a scan that’s simply filtering out risks you can’t afford to miss.

Best practices checklist

Individually, each blind spot might seem manageable. But together, they create a fragile system where even the most diligent teams can miss critical vulnerabilities – not because they’re neglecting security, but because the ecosystem itself is built on inconsistent data, differing logic, and partial visibility. That’s why it’s become so essential to understand scanning limits and compensate for them.

While you can’t eliminate every structural flaw in today’s vulnerability landscape, you can dramatically reduce your exposure by layering defenses, questioning assumptions, and shifting some of the burden away from scanners alone. The following best practices will help your team avoid chasing ghosts, overlooking exploitable code, or trusting clean reports that are hiding real risk.

Practical steps:

- Investigate “0 CVE” scan results. When you’re scanning open source images, treat every clean result as a signal to dig deeper. Verify OS detection, check advisory coverage, and make sure scanner databases are up to date before trusting it entirely.

- Run multiple scanners in parallel. Tools like Trivy, Grype, and Clair all carry different biases and leverage different data sources, so comparing outputs reduces the risk of silent false negatives or false positives.

- Use minimal, secure-by-design base images. Enterprise-grade CVE-free container images like echo shift from reactive patching to proactive prevention.

- Track software outside the package manager. Audit custom binaries, manually installed runtimes, and language-ecosystem dependencies (pip, npm, gem). Make sure they’re monitored separately since scanners can miss them.

- Rescan continuously. Advisory databases evolve daily, so it’s important to recognize that a clean report today can doesn’t mean it’ll be clean tomorrow. Be sure to establish a cadence that keeps pace with feed updates.

Final thoughts and takeaways

Vulnerability scanning will always play a role in modern security, but this ebook has shown why it shouldn’t be treated as a single source of truth. Blind spots appear at every layer – from lagging distro advisories, to missing metadata that leaves CVEs unmatched, to scanner logic that silently fails, and even to upstream CVEs that remain unresolved.

At echo, we see these gaps every day while building and validating CVE-free base images across all major scanners. Our work gives us first-hand insight into how scanners succeed, where they fail, and what security teams need to do differently. We’ve come to understand that the only way to close these blind spots for good is to address vulnerabilities at the source.

Interested in learning more about our CVE-free container base images? Let’s chat.

Request a demo

.avif)